Study Material Cost Innovation

COURTESY :- vrindawan.in

Wikipedia

Standard cost accounting is a traditional cost accounting method introduced in the 1920s, as an alternative for the traditional cost accounting method based on historical costs.

Standard cost accounting uses ratios called efficiencies that compare the labor and materials actually used to produce a good with those that the same goods would have required under “standard” conditions. As long as actual and standard conditions are similar, few problems arise. Unfortunately, standard cost accounting methods developed about 100 years ago, when labor comprised the most important cost of manufactured goods. Standard methods continue to emphasize labor efficiency even though that resource now constitutes a (very) small part of the cost in most cases Statler, Elaine; Grabel, Joyce (2016). “2016”. The Master Guide to Controllers’ Best Practices. 10 Paragon Drive, Suite 1, Montvale, NJ 07645-1760: The Association of Acccountants and Financial Professionals in Business. p. 352. ISBN 978-0-996-72932-1.“.

Standard cost accounting can hurt managers, workers, and firms in several ways. For example, a policy decision to increase inventory can harm a manufacturing manager’s performance evaluation. Increasing inventory requires increased production, which means that processes must operate at higher rates. When something goes wrong, the process takes longer and uses more than the standard labor time. The manager appears responsible for the excess, even though they have no control over the production requirement or the problem.

In adverse economic times, firms use the same efficiencies to downsize, right size, or otherwise reduce their labor force. Workers laid off, under those circumstances, have even less control over excess inventory and cost efficiencies than their managers.

Many financial and cost accountants have agreed on the desirability of replacing standard cost accounting. They have not, however, found a successor.

One of the first authors to foresee standard costing was the British accountant George P. Norton in his 1889 Textile Manufacturers’ Bookkeeping. John Whitmore, a disciple of Alexander Hamilton Church, is credited for actually presenting “…the first detailed description of a standard cost system…” in 1906/08. The Anglo-American management consultant G. Charter Harrison is credited for designing one of the earliest known complete standard cost systems in the early 1910s.

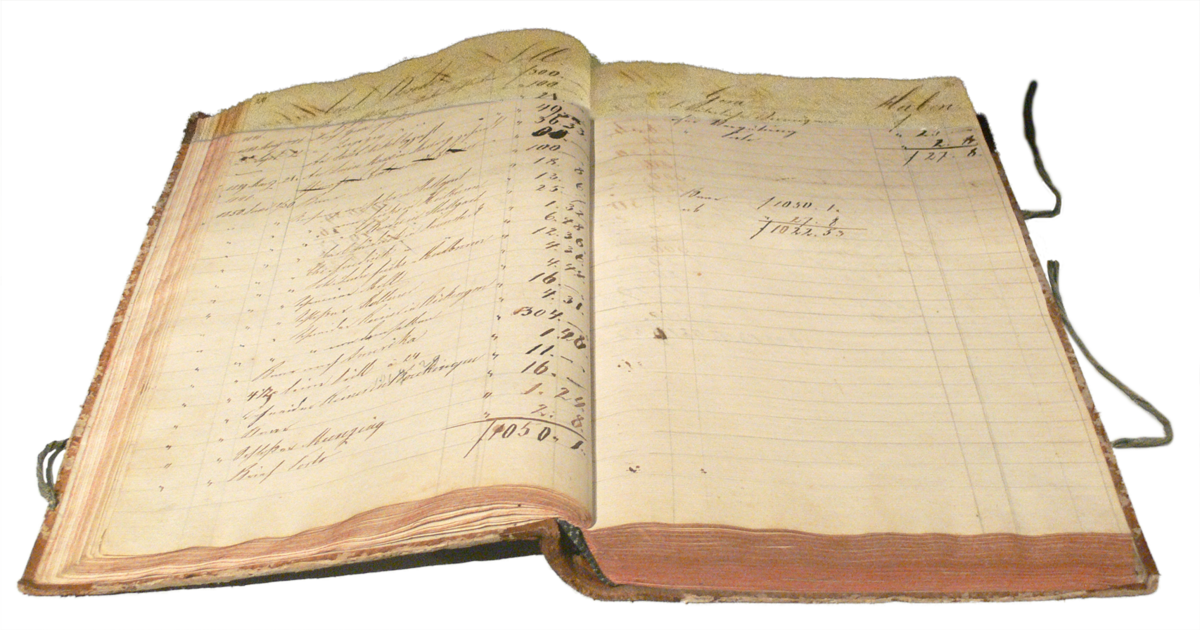

When cost accounting was developed in the 1890s, labor was the largest fraction of product cost and could be considered a variable cost. Workers often did not know how many hours they would work in a week when they reported on Monday morning because time-keeping systems (based in time book) were rudimentary. Cost accountants, therefore, concentrated on how efficiently managers used labor since it was their most important variable resource. Now, however, workers who come to work on Monday morning almost always work 40 hours or more; their cost is fixed rather than variable. However, today, many managers are still evaluated on their labor efficiencies, and many downsizing, rightsizing, and other labor reduction campaigns are based on them.

Traditional standard costing (TSC), used in cost accounting, dates back to the 1920s and is a central method in management accounting practiced today because it is used for financial statement reporting for the valuation of an income statement and balance sheets line items such as the cost of goods sold (COGS) and inventory valuation. Traditional standard costing must comply with generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) and actually aligns itself more with answering financial accounting requirements rather than providing solutions for management accountants. Traditional approaches limit themselves by defining cost behavior only in terms of production or sales volume.

Historical costs are costs whereby materials and labor may be allocated based on past experience. Historical costs are costs incurred in the past. Predetermined costs are computed in advance on basis of factors affecting cost elements.

In modern cost account of recording historical costs was taken further, by allocating the company’s fixed costs over a given period of time to the items produced during that period, and recording the result as the total cost of production. This allowed the full cost of products that were not sold in the period they were produced to be recorded in inventory using a variety of complex accounting methods, which was consistent with the principles of Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP). It also essentially enabled managers to ignore the fixed costs, and look at the results of each period in relation to the “standard cost” for any given product.

- For example: if the railway coach company normally produced 40 coaches per month, and the fixed costs were still $1000/month, then each coach could be said to incur an Operating Cost/overhead of $25 =($1000 / 40). Adding this to the variable costs of $300 per coach produced a full cost of $325 per coach.

This method tended to slightly distort the resulting unit cost, but in mass-production industries that made one product line, and where the fixed costs were relatively low, the distortion was very minor.

- For example: if the railway coach company made 100 coaches one month, then the unit cost would become $310 per coach ($300 + ($1000 / 100)). If the next month the company made 50 coaches, then the unit cost = $320 per coach ($300 + ($1000 / 50)), a relatively minor difference.

- An important part of standard cost accounting is a variance analysis, which breaks down the variation between actual cost and standard costs into various components (volume variation, material cost variation, labor cost variation, etc.) so managers can understand why costs were different from what was planned and take appropriate action to correct the situation.

- In production, research, retail, and accounting, a cost is the value of money that has been used up to produce something or deliver a service, and hence is not available for use anymore. In business, the cost may be one of acquisition, in which case the amount of money expended to acquire it is counted as cost. In this case, money is the input that is gone in order to acquire the thing. This acquisition cost may be the sum of the cost of production as incurred by the original producer, and further costs of transaction as incurred by the acquirer over and above the price paid to the producer. Usually, the price also includes a mark-up for profit over the cost of production.

More generalized in the field of economics, cost is a metric that is totaling up as a result of a process or as a differential for the result of a decision. Hence cost is the metric used in the standard modeling paradigm applied to economic processes.

In accounting, costs are the monetary value of expenditures for supplies, services, labor, products, equipment and other items purchased for use by a business or other accounting entity. It is the amount denoted on invoices as the price and recorded in book keeping records as an expense or asset cost basis.

Opportunity cost, also referred to as economic cost is the value of the best alternative that was not chosen in order to pursue the current endeavor—i.e., what could have been accomplished with the resources expended in the undertaking. It represents opportunities forgone.

When a transaction takes place, it typically involves both private costs and external costs.

Private costs are the costs that the buyer of a good or service pays the seller. This can also be described as the costs internal to the firm’s production function.

External costs (also called externalities), in contrast, are the costs that people other than the buyer are forced to pay as a result of the transaction. The bearers of such costs can be either particular individuals or society at large. Note that external costs are often both non-monetary and problematic to quantify for comparison with monetary values. They include things like pollution, things that society will likely have to pay for in some way or at some time in the future, even so that are not included in transaction prices.

Social costs are the sum of private costs and external costs.

For example, the manufacturing cost of a car (i.e., the costs of buying inputs, land tax rates for the car plant, overhead costs of running the plant and labor costs) reflects the private cost for the manufacturer (in some ways, normal profit can also be seen as a cost of production; see, e.g., Ison and Wall, 2007, p. 181). The polluted waters or polluted air also created as part of the process of producing the car is an external cost borne by those who are affected by the pollution or who value unpolluted air or water. Because the manufacturer does not pay for this external cost (the cost of emitting undesirable waste into the commons), and does not include this cost in the price of the car (a Kaldor-Hicks compensation), they are said to be external to the market pricing mechanism. The air pollution from driving the car is also an externality produced by the car user in the process of using his good. The driver does not compensate for the environmental damage caused by using the car.

When developing a business plan for a new or existing company, product or project, planners typically make cost estimates in order to assess whether revenues/benefits will cover costs (see cost-benefit analysis). This is done in both business and government. Costs are often underestimated, resulting in cost overrun during execution.

(Cost-plus pricing) is where the price equals cost plus a percentage of overhead or profit margin.