White Paper on Basics Of E-Mail. Opening Email Client

COURTESY :- vrindawan.in

Wikipedia

Electronic mail (email or e-mail) is a method of exchanging messages (“mail”) between people using electronic devices. Email was thus conceived as the electronic (digital) version of, or counterpart to, mail, at a time when “mail” meant only physical mail (hence e- + mail). Email later became a ubiquitous (very widely used) communication medium, to the point that in current use, an email address is often treated as a basic and necessary part of many processes in business, commerce, government, education, entertainment, and other spheres of daily life in most countries. Email is the medium, and each message sent therewith is called an email (mass/count distinction).

Email operates across computer networks, primarily the Internet, and also local area networks. Today’s email systems are based on a store-and-forward model. Email servers accept, forward, deliver, and store messages. Neither the users nor their computers are required to be online simultaneously; they need to connect, typically to a mail server or a web mail interface to send or receive messages or download it.

Originally an ASCII text-only communications medium, Internet email was extended by Multipurpose Internet Mail Extensions (MIME) to carry text in other character sets and multimedia content attachments. International email, with internationalized email addresses using UTF-8, is standardized but not widely adopted.

The term electronic mail has been in use with its modern meaning since 1975, and variations of the shorter E-mail have been in use since 1979:

- email is now the common form, and recommended by style guides. It is the form required by IETF Requests for Comments (RFC) and working groups. This spelling also appears in most dictionaries.

- e-mail is the form favored in edited published American English and British English writing as reflected in the Corpus of Contemporary American English data, but is falling out of favor in some style guides.

- E-mail is sometimes used. The original usage in June 1979 occurred in the journal Electronics in reference to the United States Postal Service initiative called E-COM, which was developed in the late 1970s and operated in the early 1980s.

- Email is also used.

- EMAIL was used by CompuServe starting in April 1981, which popularized the term.

- EMail is a traditional form used in RFCs for the “Author’s Address”.

The service is often simply referred to as mail, and a single piece of electronic mail is called a message. The conventions for fields within emails — the “To,” “From,” “CC,” “BCC” etc. — began with RFC-680 in 1975.

An Internet email consists of an envelope and content; the content consists of a header and a body.

Computer-based messaging between users of the same system became possible after the advent of time-sharing in the early 1960s, with a notable implementation by MIT’s CTSS project in 1965. Most developers of early mainframes and minicomputers developed similar, but generally incompatible, mail applications. In 1971 the first ARPANET network mail was sent, introducing the now-familiar address syntax with the ‘@’ symbol designating the user’s system address. Over a series of RFCs, conventions were refined for sending mail messages over the File Transfer Protocol.

Proprietary electronic mail systems soon began to emerge. IBM, CompuServe and Xerox used in-house mail systems in the 1970s; CompuServe sold a commercial intra office mail product from 1978 and IBM and Xerox from 1981. DEC’s ALL-IN-1 and Hewlett-Packard’s HPMAIL (later HP Desk Manager) were released in 1982; development work on the former began in the late 1970s and the latter became the world’s largest selling email system.

The Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP) protocol was implemented on the ARPANET in 1983. LAN email systems emerged in the mid 1980s. For a time in the late 1980s and early 1990s, it seemed likely that either a proprietary commercial system or the X.400 email system, part of the Government Open Systems Interconnection Profile (GOSIP), would predominate. However, once the final restrictions on carrying commercial traffic over the Internet ended in 1995, a combination of factors made the current Internet suite of SMTP, POP3 and IMAP email protocols the standard.

The following is a typical sequence of events that takes place when sender Alice transmits a message using a mail user agent (MUA) addressed to the email address of the recipient.

- The MUA formats the message in email format and uses the submission protocol, a profile of the Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP), to send the message content to the local mail submission agent (MSA), in this case smtp.a.org.

- The MSA determines the destination address provided in the SMTP protocol (not from the message header) — in this case, bob@b.org — which is a fully qualified domain address (FQDA). The part before the @ sign is the local part of the address, often the username of the recipient, and the part after the @ sign is a domain name. The MSA resolves a domain name to determine the fully qualified domain name of the mail server in the Domain Name System (DNS).

- The DNS server for the domain b.org (ns.b.org) responds with any MX records listing the mail exchange servers for that domain, in this case mx.b.org, a message transfer agent (MTA) server run by the recipient’s ISP.

- smtp.a.org sends the message to mx.b.org using SMTP. This server may need to forward the message to other MTAs before the message reaches the final message delivery agent (MDA).

- The MDA delivers it to the mailbox of user bob.

- Bob’s MUA picks up the message using either the Post Office Protocol (POP3) or the Internet Message Access Protocol (IMAP).

In addition to this example, alternatives and complications exist in the email system:

- Alice or Bob may use a client connected to a corporate email system, such as IBM Lotus Notes or Microsoft Exchange. These systems often have their own internal email format and their clients typically communicate with the email server using a vendor-specific, proprietary protocol. The server sends or receives email via the Internet through the product’s Internet mail gateway which also does any necessary reformatting. If Alice and Bob work for the same company, the entire transaction may happen completely within a single corporate email system.

- Alice may not have an MUA on her computer but instead may connect to a web mail service.

- Alice’s computer may run its own MTA, so avoiding the transfer at step 1.

- Bob may pick up his email in many ways, for example logging into mx.b.org and reading it directly, or by using a web mail service.

- Domains usually have several mail exchange servers so that they can continue to accept mail even if the primary is not available.

Many MTAs used to accept messages for any recipient on the Internet and do their best to deliver them. Such MTAs are called open mail relays. This was very important in the early days of the Internet when network connections were unreliable. However, this mechanism proved to be exploitable by originators of unsolicited bulk email and as a consequence open mail relays have become rare, and many MTAs do not accept messages from open mail relays.

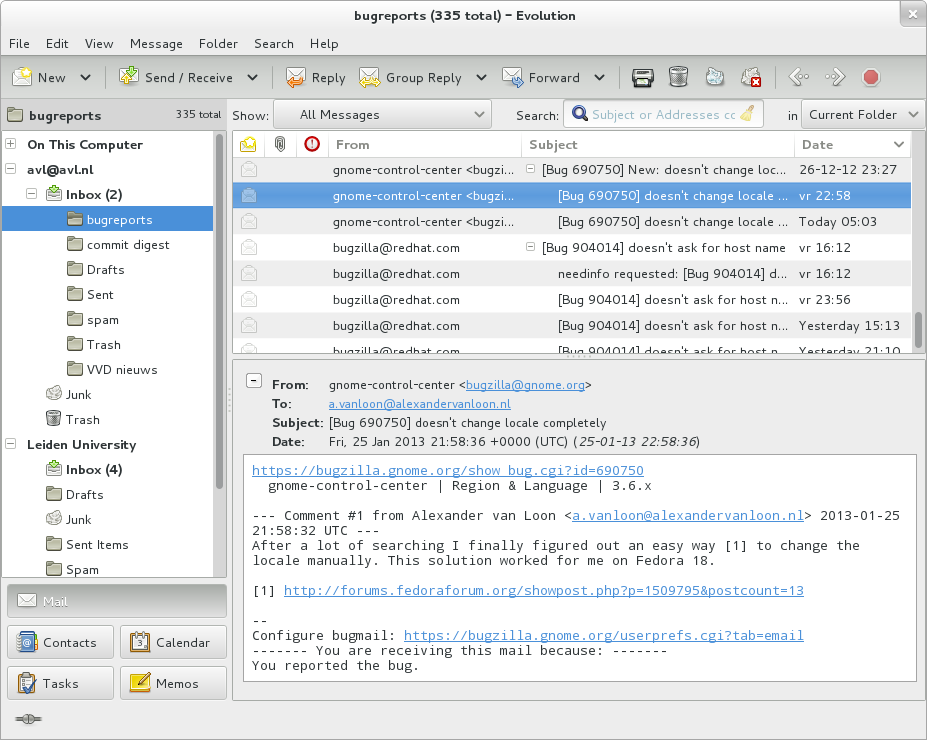

An email client, email reader or, more formally, message user agent (MUA) or mail user agent is a computer program used to access and manage a user’s email.

A web application which provides message management, composition, and reception functions may act as a web email client, and a piece of computer hardware or software whose primary or most visible role is to work as an email client may also use the term.

Like most client programs, an email client is only active when a user runs it. The common arrangement is for an email user (the client) to make an arrangement with a remote Mail Transfer Agent (MTA) server for the receipt and storage of the client’s emails. The MTA, using a suitable mail delivery agent (MDA), adds email messages to a client’s storage as they arrive. The remote mail storage is referred to as the user’s mailbox. The default setting on many Unix systems is for the mail server to store formatted messages in mbox, within the user’s home directory. Of course, users of the system can log-in and run a mail client on the same computer that hosts their mailboxes; in which case, the server is not actually remote, other than in a generic sense.

Emails are stored in the user’s mailbox on the remote server until the user’s email client requests them to be downloaded to the user’s computer, or can otherwise access the user’s mailbox on the possibly remote server. The email client can be set up to connect to multiple mailboxes at the same time and to request the download of emails either automatically, such as at pre-set intervals, or the request can be manually initiated by the user.

A user’s mailbox can be accessed in two dedicated ways. The Post Office Protocol (POP) allows the user to download messages one at a time and only deletes them from the server after they have been successfully saved on local storage. It is possible to leave messages on the server to permit another client to access them. However, there is no provision for flagging a specific message as seen, answered, or forwarded, thus POP is not convenient for users who access the same mail from different machines.

Alternatively, the Internet Message Access Protocol (IMAP) allows users to keep messages on the server, flagging them as appropriate. IMAP provides folders and sub-folders, which can be shared among different users with possibly different access rights. Typically, the Sent, Drafts, and Trash folders are created by default. IMAP features an idle extension for real-time updates, providing faster notification than polling, where long-lasting connections are feasible. See also the remote messages section below.

The JSON Meta Application Protocol (JMAP) is implemented using JSON APIs over HTTP and has been developed as an alternative to IMAP/SMTP.

In addition, the mailbox storage can be accessed directly by programs running on the server or via shared disks. Direct access can be more efficient but is less portable as it depends on the mailbox format; it is used by some email clients, including some web mail applications.

Email clients usually contain user interfaces to display and edit text. Some applications permit the use of a program-external editor.

The email clients will perform formatting according to RFC 5322 for headers and body, and MIME for non-textual content and attachments. Headers include the destination fields, To, Cc (short for Carbon copy), and Bcc (Blind carbon copy), and the originator fields From which is the message’s author(s), Sender in case there are more authors, and Reply-To in case responses should be addressed to a different mailbox. To better assist the user with destination fields, many clients maintain one or more address books and/or are able to connect to an LDAP directory server. For originator fields, clients may support different identities.

Client settings require the user’s real name and email address for each user’s identity, and possibly a list of LDAP servers.

When a user wishes to create and send an email, the email client will handle the task. The email client is usually set up automatically to connect to the user’s mail server, which is typically either an MSA or an MTA, two variations of the SMTP protocol. The email client which uses the SMTP protocol creates an authentication extension, which the mail server uses to authenticate the sender. This method eases modularity and nomadic computing. The older method was for the mail server to recognize the client’s IP address, e.g. because the client is on the same machine and uses internal address 127.0.0.1, or because the client’s IP address is controlled by the same Internet service provider that provides both Internet access and mail services.

Client settings require the name or IP address of the preferred outgoing mail server, the port number (25 for MTA, 587 for MSA), and the user name and password for the authentication, if any. There is a non-standard port 465 for SSL encrypted SMTP sessions, that many clients and servers support for backward compatibility.

With no encryption, much like for postcards, email activity is plainly visible by any occasional eavesdropper. Email encryption enables privacy to be safeguarded by encrypting the mail sessions, the body of the message, or both. Without it, anyone with network access and the right tools can monitor email and obtain login passwords. Examples of concern include the government censorship and surveillance and fellow wireless network users such as at an Internet cafe.

All relevant email protocols have an option to encrypt the whole session, to prevent a user’s name and password from being sniffed. They are strongly suggested for nomadic users and whenever the Internet access provider is not trusted. When sending mail, users can only control encryption at the first hop from a client to its configured outgoing mail server. At any further hop, messages may be transmitted with or without encryption, depending solely on the general configuration of the transmitting server and the capabilities of the receiving one.

Encrypted mail sessions deliver messages in their original format, i.e. plain text or encrypted body, on a user’s local mailbox and on the destination server’s. The latter server is operated by an email hosting service provider, possibly a different entity than the Internet access provider currently at hand.

Encrypting an email retrieval session with, e.g., SSL, can protect both parts (authentication, and message transfer) of the session.

Alternatively, if the user has SSH access to their mail server, they can use SSH port forwarding to create an encrypted tunnel over which to retrieve their emails.

There are two main models for managing cryptographic keys. S/MIME employs a model based on a trusted certificate authority (CA) that signs users’ public keys. Open PGP employs a somewhat more flexible web of trust mechanism that allows users to sign one another’s public keys. Open PGP is also more flexible in the format of the messages, in that it still supports plain message encryption and signing as they used to work before MIME standardization.

In both cases, only the message body is encrypted. Header fields, including originator, recipients, and often subject, remain in plain text.

In addition to email clients running on a desktop computer, there are those hosted remotely, either as part of a remote UNIX installation accessible by telnet (i.e. a shell account), or hosted on the Web. Both of these approaches have several advantages: they share an ability to send and receive email away from the user’s normal base using a web browser or telnet client, thus eliminating the need to install a dedicated email client on the user’s device.

Some websites are dedicated to providing email services, and many Internet service providers provide web mail services as part of their Internet service package. The main limitations of web mail are that user interactions are subject to the website’s operating system and the general inability to download email messages and compose or work on the messages offline, although there are software packages that can integrate parts of the web mail functionality into the OS (e.g. creating messages directly from third party applications via MAPI).

Like IMAP and MAPI, web mail provides for email messages to remain on the mail server. See next section.

POP3 has an option to leave messages on the server. By contrast, both IMAP and web mail keep messages on the server as their method of operating, albeit users can make local copies as they like. Keeping messages on the server has advantages and disadvantages.

- Messages can be accessed from various computers or mobile devices at different locations, using different clients.

- Some kind of backup is usually provided by the server.

- With limited bandwidth, access to long messages can be lengthy, unless the email client caches a local copy.

- There may be privacy concerns since messages that stay on the server at all times have more chances to be casually accessed by IT personnel, unless end-to-end encryption is used.

Popular protocols for retrieving mail include POP3 and IMAP4. Sending mail is usually done using the SMTP protocol.

Another important standard supported by most email clients is MIME, which is used to send binary file email attachments. Attachments are files that are not part of the email proper but are sent with the email.

Most email clients use a User-Agent header field to identify the software used to send the message. According to RFC 2076, this is a common but non-standard header field.

RFC 6409, Message Submission for Mail, details the role of the Mail submission agent.

RFC 5068, Email Submission Operations: Access and Accountability Requirements, provides a survey of the concepts of MTA, MSA, MDA, and MUA. It mentions that “ Access Providers MUST NOT block users from accessing the external Internet using the SUBMISSION port 587” and that “MUAs SHOULD use the SUBMISSION port for message submission.